On

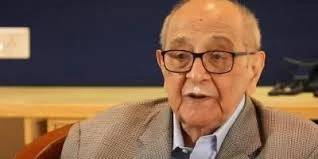

May 3, 2025, 94-year-old Warren Buffett announced his retirement as CEO of

Berkshire Hathaway at its annual shareholder meeting, surprising many.

**

Warren Buffett, the legendary investor known for his

preternatural value investing, who previously said that he had no intention of

retiring, realized that the time had come “to act fast” and announced that he

would step down as CEO of Berkshire Hathaway at the end of 2025 and pass on the

baton to Greg Abel, Vice Chairman, who is currently overseeing Berkshire’s

non-insurance business.

In 1965, Buffett acquired Berkshire Hathaway, a struggling textile manufacturer, and transformed it into a global conglomerate holding company that manages a diverse range of businesses and investments. Its main business is insurance—both direct and reinsurance. He turned it into the world’s biggest reinsurer. It also manages freight rail transportation and utility and energy distribution. Besides these core businesses, the company also owns dozens of well-known consumer-oriented companies in various sectors. It also has significant stakes in other publicly traded companies.

Buffett’s entrepreneurial journey started quite early in life. As a school-going boy, Buffett started investing in stocks with the money earned by delivering newspapers. It is at Columbia University that he mastered the art and science of valuing stocks under the mentorship of the legendary Benjamin Graham—“father of value investing”. Since then, he has spent his lifetime in search of businesses that offer scope for growth and stability.

Buffett said that all through his investment career, he has practiced a cardinal principle: Never invest in a business that you don’t understand its business model. He is known for being wary of investing in technology firms, simply because he claims not to understand the tech business. Intriguingly, he doesn’t own any stake even in Microsoft, although he has partnered with Bill Gates on the bridge circuit.

As is well known, insurance businesses generate large volumes of cheap cash in the form of premiums collected. While the insurance business is in itself a very profitable one, it is the wise deployment of that cash by Buffett in the stock market that has made Berkshire consistently generate high returns from the investments. Today, the company enjoys a market value of $1.08 tn plus. Berkshire Hathaway is now the world’s eighth most valuable company. Buffett’s personal stake in the company stood at around $168 bn, making him the world’s fifth-wealthiest man.

Buffett’s investment philosophy is pretty transparent. As a well-known value investing strategist, he did not participate in the dotcom boom of the late 1990s, for he thought that those companies were overvalued based on speculation rather than financial performance. Thus, he was able to avoid the kind of heavy losses that many other investors suffered when the dotcom bubble imploded in the early 2000s.

Buffett claims that the secret of his investment strategy is: Patience. He patiently waits until he thinks the price is right to buy a stock. As and when the price is considered right by Berkshire, it will buy a big stake and allow the incumbent management to carry on the business with little or no oversight from it.

Buffett’s sharpness in understanding complex financial business models is well reflected in the portfolio that he builds up, mostly driven by his own financial valuations. Berkshire’s investment portfolio predominantly includes consumer-centric businesses such as Coca-Cola, Bank of America, and Apple, besides a substantial stake in the financial sector.

Eugene Fama, a Nobel Laureate in economics from the United States, proposed the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), which suggests that stock prices fully reflect all available information, making it impossible to consistently outperform the market. The theory posits that if all information is instantly and accurately incorporated into stock prices, there is no way to find undervalued stocks or consistently beat the market through expert stock selection or market timing, except perhaps by buying riskier investments. It essentially means that one can earn only market-average returns unless one has access to non-public information. But Buffett has challenged the EMH through his value investing approach, which focuses on identifying undervalued stocks and holding onto them for a long time. His Berkshire Hathaway’s annualized return on investment during 1965-2024 is estimated to be around 19.9% as against 10.4% of S&P 500 annualized return for the same period.

Buffett used to share his deep insights and the sharpness of his stock-picking strategy in the form of aphorisms couched with humor through his letters to shareholders, as also in his address at the annual general body meetings. He once cautioned investors, saying, “If you are trying to trade on headlines or time the market, you are not investing—you’re gambling”.

In 2003, Buffett shared his opinion against derivatives through Berkshire’s annual report: “In my view, derivatives are financial weapons of mass destruction, carrying dangers that, while now latent, are potentially lethal”. He also highlighted the potential of these complex instruments to cause systemic risk, particularly due to opaque pricing and accounting practices. He even said: “... the parties to derivatives also have enormous incentives to cheat in accounting for them”. And come 2008, the collapse of AIG, a major issuer of Credit Default Swaps (CDS), and the global economic crisis proved how prophetic Buffett was.

Once Buffett saying, “the risk-averse investor is the poor investor”, encouraged retail investors to take calculated risks, but only in areas where one has a good understanding of the business. One of his famous pieces of advice is: “It’s far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price”.

Backed by long years

of experience gained from Wall Street, he once gave a sagely advice to the

retail investors: “Volatility is a feature of stock markets, not a bug”. He

summarizes that in the next 20 years, there may come a phase that will be a

“hair curler” compared to anything we have seen before. Such events keep

recurring, and these typically unfold in dramatic ways. But that is just the

way of the stock market. This unpredictability makes the stock market a

great place to invest in, but only if one has the temperament for it. On the

other hand, it is not a good space for those who get frightened by markets that

decline and get excited when stock markets go up.

On Donald Trump winning the elections, most of the stock market participants turned euphoric and the US equities, bonds and currency markets rallied strongly immediately after the results. But the Oracle of Omaha, turning more oracular, and guessing that once Trump starts fulfilling campaign promises, markets may face turmoil, Berkshire Hathaway sold its profitable positions. Strategically, it sold more shares than it bought in 2024, and as a result, it is sitting on cash and cash equivalents and short-term investments of $333.3 bn in December 2024, which is almost double the cash reserves—$167.5 bn—held in December 2023.

As perhaps wary of market uncertainties stemming from Trump’s tariff war, Buffett appeared to prefer investing in low-yielding US Treasury bills rather than stocks. In uncertain times, cash can serve as a handy cushion—and times have rarely been as uncertain as during the ongoing tariff-mayhem. However, some analysts argue that clinging to such a large cash reserve carries a significant opportunity cost, leading them to question the legendary investor’s decision to stay away from Wall Street.

However, in his annual letter to shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway, Buffett addressed this dilemma: “We are impartial in our choice of equity vehicles, investing in either variety based upon where we can best deploy your (and my family’s) savings. Often, nothing looks compelling; very infrequently, we find ourselves knee-deep in opportunities”. This candid approach is one of the admirable traits of Berkshire Hathaway and its Chairman, who openly discusses the company’s challenges and decisions in his annual letters to shareholders.

Enriched by decades of experience in the investment world, Buffett sounds very forthright when he says, “The problem with the investment business is that things don’t come along in an orderly fashion, and they never will”. He goes on to say that “Berkshire holding large amounts of cash isn’t out of fear but out of discipline and patience, waiting for good opportunities. When those come, having the cash to pounce on the opportunity matters”.

This legendary investor’s philosophy of philanthropy is “grounded in his belief that those with great wealth have a responsibility to give back to society”. His philanthropy is characterized by unprecedented scale and a focus on effectiveness. He preferred to give donations to existing foundations rather than starting new ones. He has been the largest individual donor to the Gates Foundation, contributing over $43 bn as of 2024. With a lifetime charitable giving that exceeds $56 bn, Buffett stands as one of the top philanthropists. He pledged to give away 99% of his remaining wealth to a charitable trust managed by his three children after his death.

That is Buffett and his investment

philosophy. This philanthropist’s impending retirement will mark the end of an

era. His philanthropy, however, blooms forever.

**

.jpg)