With the reforms launched and pursued by different political regimes at the center, globalization has become a reality. Its impact on various segments of the economy is felt differently by different sections of the society. This article analyzes the growth experience in India since the 1991 reforms in terms of theoretical, empirical and policy experiences and aims to map the challenges to, and the inadequacies of, ‘job reservations’ in ensuring ‘efficiency’ in our economic endeavors and welfare of the human capital. It also suggests a policy framework to counter these threats.

I. Introduction

Globalization, as an ideology, connotes freedom and internationalism. It helps realize the benefits of free trade, and thus comparative advantage and the division of labor. It is supposed to enhance efficiency and productivity (Edward S Herman, 1999). It is therefore considered as both an opportunity and a risk. It is an opportunity if only one could master the craft of doing business at increased levels of ‘efficiency’. On the other hand, if the economy is plagued with inefficiencies, there is no greater risk than globalization. It has ushered in the era of changing paradigms: A shift from financial capital to intellectual capital; horizontal/vertical to virtual; and time-tested procedures to innovation. In such a scenario what matters most is the ‘human capital’. As Drucker (1990) argues, we are living in a new world of ‘relatives’. In this new world, a new process of internationalization and the spread of international production has emerged in which human resources are required to be knowledgeable, committed, and willing to walk that extra mile for the collective good of the businesses. To survive in global competition, businesses will have to adopt the best HR policies such as performance-linked rewards and career progression to attract and retain the talent, more under the fear of being cannibalized otherwise. Globalization has thus become a major environmental change (McGee and Howards, 1988). It demands that states and firms have to modify their tactical decision to accommodate such extraordinary environmental change (Ronen Palan and Jason Abbott, 1996).

As against these emerging requirements, caste system in India is still working as a social barrier separating people into economic and social strata due to birth, reinforcing discrimination in individual statuses. Discrimination on the basis of gender, ethnicity or social status is still leading to social exclusion, causing greater deprivation among the less privileged. It is to overcome these social and educational disadvantages faced by the “low-caste people” that the Government of free India reserved a large share of government sector jobs for Scheduled Castes and Tribes and others in the lower strata, besides helping lower-strata people access educational facilities on a special footing.

Amidst these ground realities, we, having pursued an “inward-looking” development strategy with the State at the center for almost four decades, embarked on a reform drive during 1990-91that transformed us from a regulated to a fairly open economy. The launching of first generation reforms, through which India is attempting to get more and more integrated with the world economy, is demanding ‘human efficiency and competency’ for the very survival of businesses that are today facing stiff competition, both from domestic and overseas market players. The emerging demand for efficiency in workforces is likely to threaten the existing reservation policies that encourage employment on ‘affirmation-principle’ than on merit alone.

Against this backdrop, the present article examines the phenomenon of globalization and its role, if any, in generating growth; globalization-induced disinvestment of public sector undertakings and its impact on employment generation; the ultimate threat to ‘job-reservations’ across the country and what the state should do to diffuse the negative fall-out from the ongoing globalization. The rest of the article is structured on the following lines: II. Globalization: A fact or option?; III. Globalized economy and the demand for efficiency; IV. Globalization and the challenge posed to Reservation Policy and vice versa; V. Challenge to Reservation Policy: What then State should do; and VI. Conclusions.

II. Globalization: A Fact or Option?

Globalization is a process by which producers and consumers come to treat the world as a single economic space. It leads to widening horizons, increased specialization and interdependence that has of course been taking place within countries for hundreds of years. What Adam Smith thought of self-generating economic growth within a single country is now being contemplated at the global level. Interaction of countries through trade not only expands the market but makes the gains interactive: “A’s” enrichment expands B’s market, which enriches ‘A and “A’s enrichment expands ‘B’s’ market, which enriches “B”. Thus, globalization generates ‘wealth spiral’ that brings benefits to all. Globalization supposedly enhances efficiency and productivity.

‘Globalization’ is subtly referring to growing interdependence across the world on a number of dimensions that are pretty divergent. On the other hand, it is also being frequently used to denote globalization of institutions, collectivities and practices. So, what is needed in the current fuzzy world of globalization is ‘lifting’ or the ‘disembedding’ of structures and activities from local ‘context’ to global context. This thinking has indeed coined a new phrase: ‘Think globally and act locally’. This phrase is of great importance here sociologically: It paves the way to link the local problems to the global, suggesting that local problems can better be solved in a wider context. That is what perhaps is driving the developing countries today to better the lot of their teeming population by attempting at ‘growth’ through globalization.

The resultant ‘growth’ from the ongoing reforms is supposed to create jobs that ‘pull up’ the poor into gainful employment by providing more economic opportunity; it provides the revenue with which the government can build more schools and provide more health facilities for the poor; and it creates the incentives that enable the poor to access these facilities and also for the advancement of progressive social agenda (Jagdish Bhagwati, 2002).

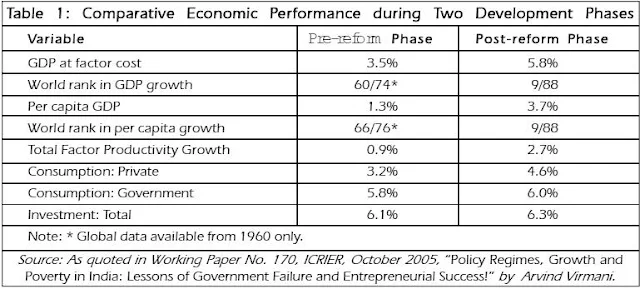

Growth is thus essential for advancement of social agendas. To create ‘supply response’; to build schools, pay teachers better salaries, etc., a country needs resources which a growing economy alone can provide. Similarly, empowerment of women through economic alternatives is feasible only in a rapidly growing economy. And the fact that the growth is now achievable in a globalized economy has been amply indicated by the performance of Indian economy since liberalization. During 1992-93 to 1998-99, our average annual growth rate stood at 6.55%, which is higher than the previous high of 6.4% achieved during the period 1985-86 to 1989-90. The average annual per capita income growth rate between 1992-93 and 1998-99 has been 4.7% as against 3.4% in the 80s. The current account deficit has remained low at an average 1.3% of GDP since 1992-93 (C Rangarajan, 2002). The following figures representing the performance of Indian economy during pre- and post-reform phases do reflect the positive impact of globalization on the macroeconomic fundamentals:

Globalization is thus no more an option for India. It has become a reality and if we juxtapose the current happenings in India with the characteristics of globalization defined by Michael Porter (1990)—namely, growing similarity of countries; fluid global capital markets; falling tariff barriers; technological restructuring; integration role of technology; and new global competitors—one has to admit that globalization has become a reality in India. Globalization has today enabled Indians to mobilize capital from anywhere in the globe at cheaper prices, subject of course to regulations for investment either in our domestic market or abroad. This free movement of capital, information and knowledge has of course paved the way for simultaneous transfer of ‘threats’ and ‘opportunities’ from a country or countries with which we are more connected. Now, what else we need to admit that globalization has become a reality with us?

In appreciation of these prospects and to be a competent player in the global market, majority of the nations are reorienting themselves towards the required ‘connectedness’ with each other and within that ‘oneness’ trying to carve out ‘uniqueness’ and thereby proving themselves better than the rest. India is already on that path. However, globalization can cast its shadow zone on the already poor by alienating them further from the main stream because of their poor skills but not due to lack of opportunities. Such differences are of course likely to weaken once the real benefits of ‘growth’ trickle down to lower strata. Similar observations were echoed in what the study of Deshpande and Deshpande (1996) revealed: Although employment in organized manufacturing sector was hit in the initial period of transition, the subsequent structural adjustment resulted in an employment growth rate of 2.3% between 1992 and 1995. Nevertheless, ‘growth’ requires complementary policies, where necessary, to prevent hurtful outcomes or to offset them as and when they show up. Hence, he recommends such reforms that would reverse anti-globalization, anti-market, pro-public-enterprise attitudes and policies (Bhagwati, 2002).

In appreciation of these prospects and to be a competent player in the global market, majority of the nations are reorienting themselves towards the required ‘connectedness’ with each other and within that ‘oneness’ trying to carve out ‘uniqueness’ and thereby proving themselves better than the rest. India is already on that path. However, globalization can cast its shadow zone on the already poor by alienating them further from the main stream because of their poor skills but not due to lack of opportunities. Such differences are of course likely to weaken once the real benefits of ‘growth’ trickle down to lower strata. Similar observations were echoed in what the study of Deshpande and Deshpande (1996) revealed: Although employment in organized manufacturing sector was hit in the initial period of transition, the subsequent structural adjustment resulted in an employment growth rate of 2.3% between 1992 and 1995. Nevertheless, ‘growth’ requires complementary policies, where necessary, to prevent hurtful outcomes or to offset them as and when they show up. Hence, he recommends such reforms that would reverse anti-globalization, anti-market, pro-public-enterprise attitudes and policies (Bhagwati, 2002).

III. Globalization, Competition and the Demand for ‘Efficiency’

“Economies of scale” result from the increased size of a single operating unit producing a single product reduces the unit cost of production (Chandler, 1990), with benefits for both producers and consumers, which can be achieved better from a market that spreads across a group of countries than in isolation. This is one of the major driving forces behind the emergence of globalization and essentially a competitive player in the domestic market alone can become the winner in global market. De Melo, et.al (1990) argue that technological diffusion is more prone to be rapid when increased competition from trade puts pressure on domestic firms to adopt new technologies. Such heightened competition forces businesses to innovate and adopt efficient technologies and managerial strategies that then place them in a better competitive position in the world economy (Chandler, 1990). Globalization thus generates economies of scale which in turn facilitate emergence of efficient, market-responsive, economic actors which ultimately benefits both consumers and producers. The net result of the whole process is the emergence of world-class economic champions and larger markets as the creators of an “enabling” environment for growth.

The progress and prosperity of an economy even in such an “enabling environment” is largely dependent on the social norms and institutions of a country. The citizens’ attitude towards work, their level of mutual trust, standard of ethics and social norms form the foundation for economic activity and prosperity of the society. It is only when individuals maximize their own selfish utility that the resulting competitive equilibrium can become Pareto-optimality. In this context, economists often advise that governments should help build human capital since a substantial portion of growth in any economy has been attributed to human capital accumulation and this is more so in a globalized economy. Thus, ‘Human Resources’ becomes the critical player. Knowledge Economy demands ‘efficient’ workforce. And ‘efficiency’ alone can lead to ‘Growth’ in a highly competitive market. The nation must provide excellent educational system to all. We need to assemble large pool of science and technology personnel. A system supporting research on merit must be initiated and encouraged. Organizations must have “outward orientation”. A knowledge-driven society is a must in knowledge economy.

Debates are going on about the extent to which societies should become global and the degree to which they should modify their practices and policies to make ‘globalization’ work better for them. Amidst these upcoming demands for ‘homogeneity’ and ‘uniformity’, what is most baffling is that countries have also to maintain a kind of ‘uniqueness’ about themselves in order to succeed in the global economy. As Sztompka (1990) observed, the emphasis is currently shifting to the alternative types of comparative inquiry: “Seeking uniqueness among the uniformities, rather than uniformity among variety”. And that ‘uniqueness’ has to be more in the form of greater ‘competency’ than that in the rest of the globe, at least in the chosen field, so that the country can enjoy ‘comparative advantage’ over others which can ultimately differentiate its output from that of others and generate market share.

Debates are going on about the extent to which societies should become global and the degree to which they should modify their practices and policies to make ‘globalization’ work better for them. Amidst these upcoming demands for ‘homogeneity’ and ‘uniformity’, what is most baffling is that countries have also to maintain a kind of ‘uniqueness’ about themselves in order to succeed in the global economy. As Sztompka (1990) observed, the emphasis is currently shifting to the alternative types of comparative inquiry: “Seeking uniqueness among the uniformities, rather than uniformity among variety”. And that ‘uniqueness’ has to be more in the form of greater ‘competency’ than that in the rest of the globe, at least in the chosen field, so that the country can enjoy ‘comparative advantage’ over others which can ultimately differentiate its output from that of others and generate market share.

The expected growth from the ongoing reforms processes could be realized provided we change our policies and laws that are stifling ‘competency’ to claim comparative advantage. Maintenance of efficiency in production is said to be constrained by our existing Labor laws (Montek S Ahluwalia, 2002) that are quite inflexible. According to Ahluwalia, our laws that are known to protect existing employment are actually discouraging creation of new employment. Even the study of Fallon and Lucas (1991) showed how employment would have been higher in industrial sectors had there not been these inflexible laws. This could run when the economy was closed since costs, owing to inefficiencies, could be coolly transferred to consumers but he opines that it is no longer feasible under ‘open economy’, where competition from overseas markets in terms of imports challenge the very survival of businesses. Even otherwise, the labor in the organized sector being only 8% while the balance 92% is from unorganized sector, majority of the labor hardly gain any benefit from the existing archaic laws. There is thus a need for amending the labor laws to ensure efficiency in the industry. In one of his studies, Mathur (1992) recommended for removal of these restrictions and advised to draft an economical ly and socially acceptable ex i t pol icy for employees of unprofi table enterprises—including that of the government-owned. An extension of this analogy questions the very scope for continuing the prevailing ‘job-reservation’ policies that facilitate employment on considerations other than merit which by its very nature dilutes competency.

Intriguingly, as early as in 1993, when globalization is taking roots, Jackson observed that “there are a large number of states in the world that are for all intents and purposes going nowhere, and do not look like they will ever be going anywhere. It is not so much that they do not wish to pursue strategies of development but they are incapable of doing so.” Now, the moot question is what is it that enables some countries to participate in the global competitive game while it excludes others? The answer is of course simple: Only, the country, which offers a favorable climate for domestic and international investments duly supported by infrastructure in terms of “competition state” and “competitive strategies”, is likely to enable its firms compete in global markets. The “efficiency” of human capital is one of the prime builders of a competitive state and India cannot be an exception to this. What is therefore needed is that the state should provide institutional support for augmenting human capital efficiency upon which the businesses can compete in the global markets. And this is in direct contrast with our current practices of reservation policies.

IV. Globalization and Challenges to ‘Reservations Policy’ and Vice Versa

Even after five decades of Independence, the caste system in India is as powerful a social barrier separating people into economic and social strata due to birth, reinforcing discrimination in individual statuses, as it was in the past. Despite periodic challenges from social reformers, this rigid hierarchy has remained intact and even today once in a while raises its ugly head in all walks of life. The resultant social fragmentation and conflict is still strong in the Indian society. The attempts made by the government to transform the social system by abolishing untouchability in private or public behavior are yet to bear fruit. The reservation of seats in the national parliament and the state assemblies for members of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes etc. has not made any change in the outlook of the common man. Various developmental policies that were drafted and implemented to help lower caste people gain access to education for upward mobility have hardly made any dent. Even the reservation of large shares of government sector jobs for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes and other lower caste people, effected with a view to reduce the social and educational disadvantages faced by the lower caste people, is reported to have made no marked difference (Table 2).

Ironically, this well-intended corrective measure, implemented on a ‘group-basis’, has indeed created more simmering discontent among those who are outside the reservations, particularly when it comes to admissions into educational institutes. Awarding these rights, though rightly, to the hitherto deprived classes, questions the rightful entitlement, based solely on competency, of those hailing from the higher castes. This deprivation from securing a high-paying job despite an applicant’s credentials, and that too for an individual who is not responsible for what the lower castes have been subjected to in the past, has indeed created resentment among the upper caste youth. As against this, some sociologists argue that many opportunities emerging from affirmative action have not gone to the truly deserving. Most of these gains were said to have been garnered by a few already privileged from the reserved backgrounds.

There is also another opinion that availability of admission to colleges or jobs for a few tens of thousands of people looks minuscule in comparison with the deprivations faced by the millions of people. The other section that is outside the reservations lament that reservation at the expense of more meritorious others is undesirable. With the progres of time, this ‘affirmative action’ has, however, become contentious since it resulted in a kind of ‘reverse-discrimination’.

It is in order here to recall A H Hanson’s observations made around 40 years back on the decay and deterioration that took place in public services: “For various reasons, Indian planners have never treated the ‘objective function’ with sufficient respect. Their tendency is to give themselves the fullest benefit of every possible doubt… too many of their aims are contingent upon the adoption, by various sections of the Indian community, of attitudes they are exceedingly unlikely to adopt.” These observations are perhaps equally applicable to implementation of affirmation policies.

It is in order here to recall A H Hanson’s observations made around 40 years back on the decay and deterioration that took place in public services: “For various reasons, Indian planners have never treated the ‘objective function’ with sufficient respect. Their tendency is to give themselves the fullest benefit of every possible doubt… too many of their aims are contingent upon the adoption, by various sections of the Indian community, of attitudes they are exceedingly unlikely to adopt.” These observations are perhaps equally applicable to implementation of affirmation policies.

There is a gnawing fear that “reverse discrimination”, which is all along simmering under the lid is likely to become more open and vocal, in a knowledge economy. As is known, IT is India’s unique competency in the global market. If we have to retain this lead and leverage on it for future growth, the industry can hardly afford anything other than excellence in skills-profile of its workforce with a concomitant commitment to work. Any dilution in merit is more likely to generate discontentment in the workforce, leading to poor quality output which is potential enough to drive our firms out of global market overnight. Reservation policies which enable a less skilled person walk over an otherwise competent person to chair a job is bound to shrink the competency levels across the organizations making businesses less competitive in the global context. This phenomenon, whether we like it or not and desirable or undesirable, is quite certain to challenge the current reservation policies as we march further into ‘globalization’. As businesses get sensitized more and more to the globalization and its demands for ‘competitiveness’, they may sidetrack these policies.

The process of globalization is already impacting the public sector manufacturing giants. To achieve efficiency and market ‘competency’, they are being privatized. Privatization automatically leads to loss of control of the administrative ministry over the erstwhile public sector undertaking. Simultaneously, they would be granted commercial autonomy and flexibility to make them competitive in the market. The private sector is no exception to the growing demand for ‘competency’. Under the threat of being punished for inefficiencies under globalization, the businesses will go all out to attract talent from any corner of the globe. No wonder if tomorrow, Indian businesses go all out in recruiting non-Indians for leveraging on diversity while functioning at multi-locations.

The phenomenon of efficiency impacting employment opportunities in general and people endowed with mediocre skills in particular appears to have already come into force: Share of employment in PSUs during 1990-2001 is 70% of the total employment under organized sector; during 1990-2001 growth in employment in PSUs is stagnating at 1.9%; and since 1998 it is showing negative growth. The growth in private sector employment is 14.11%. The empirical study carried out by Mohan R (2004) reveals that growth rate in employment and economic growth has no statistically significant relationship. During eighties when growth rate was 5.5% per annum the rate of growth of employment grew at a reduced rate of 1.8% per annum as against 2.75% during 1972-73 to 1977-78. It is also reported that during 1994-2000, the rate of growth of employment has still further gone down. The author also commented that there was a steep increase in labor productivity in the service sector during 1994-2000. According to Ahluwalia (1992), the capital labor ratio and labor productivity increased at 8% and 7.5% respectively during the period 1980-81 to 1988-89, duly accompanied by a decline in employment growth. All this points to a future where employee productivity will be going up and as the competition increases from global players, employment growth rate is likely to slide further in general, but particularly for those who are not endowed with market-required skills.

In the globalized economy, it is the richly talented who take away all because, they can sell their services in the global market place. But those who are little less talented or not skilled at all, can at best sell themselves in the local market and hence, tend to earn much less. The gap between the first placed and the last placed is thus getting incredibly wide. A classic example of this phenomenon is the young “Indian geeks” who have become rich and are becoming richer, while the traditional labor are stagnating at the same level. It is to counter these inegalitarian trends, Anders Solimono (1999) called for such public policies that can correct them. This emerging reality has another dimension: Placing together such highly endowed and poorly skilled employees in a team that is assigned the task of, say, development of a software package simply derails it, for the highly talented individuals resent the presence of poorly skilled, considering them as a drag on the team performance. Such poor “hygiene” at work places pulls down the overall efficiency of the businesses. This no corporate will ever be prepared to entertain which again means poor employability for those who are endowed with less skills. This would obviously be dissented by corporates who are, as observed by Debashish Bhattacherjee (2000), already besieged by the absence of procedural environment required for competitive industrial pluralism to work at its best.

Businesses, while competing for a share in the highly competitive global market, look for qualified knowledge workers for improving their product differentiation. This automatically calls for excellence in educational system. The function of education system then becomes more of generating ‘employable’ graduates which means imparting cutting edge education. This may again lead to admission of students on merit rather than on any other consideration. Globalization thus appears to be all set for challenging reservations as they are prone to threaten ‘competency’ in the global arena and demand excellence in every walk of life. In fact, we must get ready to accept that globalization will simply shift power from the state and its bureaucracy to the private sector and entrepreneurs. And the affected parties of this shift could be anyone—right from the businesses which are currently enjoying the protection from the government or the labor unions which are negotiating for more remuneration and for fewer hours of work, etc. to the poorly skilled labor. This fact is well reflected in the IT industry which somehow has avoided stifling regulations that regulate working hours and overtime in all other sectors. They have been also allowed to receive foreign direct investment[1].

Klein Lawrence (2004) while analyzing the economic growth and the underlying issues thereof in China and India, identified the ‘intervention of bureaucracy’ as the obstacle for India’s continuing economic expansion. He opined that in the highly competitive global economy, slow reaction movement will hold back many potential players, and India should reconsider the place of class-society in future development.

V. Challenges to Reservation Policy: What Should the State Do?

Globalization has created new dynamics: It has democratized technology, finance and information (Thomas L Friedman, 2000). No government is today in a position to prevent its people from knowing what life across the globe is. More than governments, today it is the millions of small investors who are driving the global financial markets with a click of the mouse. Similarly, the innovations in technology achieved since the 80s in the field of computerization, telecommunications, digitization etc., are today available to every body and in fact India is enjoying the fruits of these innovations, with little or no time lag. But within all this development there is also a lurking fear: How to strike a balance between global integration and local identity, and how to manage the negative effects of globalization in terms of growing gap between the highly endowed sections and of those who are socially disadvantaged. That is where the role of state becomes critical. In the era of globalization, it is the quality of state in terms of legal system, financial system, educational system, welfare system and ultimately the management of economy that matters.

The poor people lack not only money but also resources, opportunities and access to basic necessities such as health and education. There is already a huge mass of educated youth registered with employment exchanges across the country for jobs (see Table 3). Against these realities, if the businesses in their pursuit for talent as dictated by globalization ignore the claim of less endowed youth for jobs, particularly those hailing from the hitherto “reserved

sections”, the plight of the weaker sections is bound to worsen further. This can generate social unrest and may even threaten the very social fabric. Here, it is worth remembering what Will Durant said: “No society can survive if it allows its members to behave towards one another in the same way in which it encourages them to behave as a group toward other groups; internal co-operation is the first law of external competition”. So, the state must activate its “use of state power and responsibility towards the ends of protecting citizens against economic adversities and ensuring a certain standard of prosperity to all”. It is only upon providing such a cushion that it can realign its human resources with the singular goal of winning global competition that is essential for sustaining economic growth.

The handling of such a daunting national task calls for no less than Vivekananda’s vision for the country. It is said that when he was returning from England a fellow passenger told Vivekananda that India is very moral and very ethical for there is no crime in the country. On listening this tribute, Vivekananda reported to have heaved a sigh and said: “I wish it were otherwise; I wish there is some crime in my country!” In his exclamation, what Vivekananda meant was that India was in deep ‘inertia’. There was no life, no energy, and no power to do good or evil. Everything was static. Being stagnant, India cannot but get crushed ruthlessly by the exploiters, without any energy to protest. He lamented that whatever goodness was there was largely formal, caste-dictated without the power of conviction. No wonder, these comments are equally applicable to today’s India. To beat this stagnation, Vivekananda desired that our people should achieve that dynamism of a true ethical and moral life. He wanted people of India to be awakened from that inertia by acquiring energy, activity, and dynamism. He simply wanted the people to ‘arise and awake’ and function with awakened resistance to oppression and exploitation. Having once acquired that energy, he advised the people of India to “give a discipline to it, make it creative and constructive, channelize it to man-making and nation-building purposes” (Swami Ranganathananda, 1986).

The handling of such a daunting national task calls for no less than Vivekananda’s vision for the country. It is said that when he was returning from England a fellow passenger told Vivekananda that India is very moral and very ethical for there is no crime in the country. On listening this tribute, Vivekananda reported to have heaved a sigh and said: “I wish it were otherwise; I wish there is some crime in my country!” In his exclamation, what Vivekananda meant was that India was in deep ‘inertia’. There was no life, no energy, and no power to do good or evil. Everything was static. Being stagnant, India cannot but get crushed ruthlessly by the exploiters, without any energy to protest. He lamented that whatever goodness was there was largely formal, caste-dictated without the power of conviction. No wonder, these comments are equally applicable to today’s India. To beat this stagnation, Vivekananda desired that our people should achieve that dynamism of a true ethical and moral life. He wanted people of India to be awakened from that inertia by acquiring energy, activity, and dynamism. He simply wanted the people to ‘arise and awake’ and function with awakened resistance to oppression and exploitation. Having once acquired that energy, he advised the people of India to “give a discipline to it, make it creative and constructive, channelize it to man-making and nation-building purposes” (Swami Ranganathananda, 1986).

It is for the governance of the country to channelize the peoples’ energy and power into a disciplined, organized, refined way and give a humanistic direction so that people could of their own volition cooperate with each other in meeting the challenges emanating from ‘globalization’ and achieve economic prosperity. The government should work towards eliminating ‘discrimination’ and ‘reverse discrimination’ from the society so that all could work in unison towards nation building. Such unison of energies is only possible when the government builds institutions that can afford a means to acquire the essentials of life to the ‘less-endowed’ sections of the society that in turn encourages them to ‘re-brand’ with newer skills for seeking employment in the globalized economy. It is to fully use the opportunities opened up by economic reforms, Amartya Sen[2] suggested that economic reforms must be followed by commensurate social opportunities in terms of more schooling, better healthcare, greater availability of micro-credit and more land reforms.

The study carried out by Rudra and Nita (2002) on 53 Less Developed Countries (LDCs) from 1972-95 shows that welfare spending in these countries does indeed respond to greater trade flows and capital mobility. They observe that growing numbers of low skilled workers, coupled with large surplus labor population, exacerbate the collective-action problems of labor in LDCs and make it increasingly difficult for them to organize. It is also found that when confronted with the pressures of globalization, workers in LDCs are less capable of demanding their welfare benefits than workers in OECD countries, where the organizing potential of labor is relatively strong and existing institutions can help the workers to overcome their collective action problems. As we are moving fast in the path of globalization, these findings “suggest an important cautionary note”. Much of India’s successful development depends on our “ability to utilize labor capacity, upgrade the skills of workforce, and foster the development of strong political institutions”. So, what is needed now is not ‘job reservations’ but initiation of appropriate measures to tackle these factors.

Globalization that has democratized technology, finance and information no longer affords the comfort of fooling the less-privileged with reservations which are any way not making any dent in their lives. The state should therefore aim at creating “trampolines” across the country which can offer the cushion for all those who get laid-off by the businesses or not getting employment. As a part of the proposed “trampoline architecture”, the state must also create “community vocational training centers” that can retrain those who lost their jobs and make them re-employable. These centers must design curriculum and impart training in such a way that the citizens are helped to re-equip themselves with new skills, much before they become redundant in the job market.

The recently reported move of Maruti Udyog Ltd. to establish a chain of driving schools across the country to turn out well-trained and quality drivers into market is a pointer in right direction. Such private participation in making the labor better employable needs to be encouraged by government, if required, even with fiscal concessions. In all these efforts, what is required more is agility: China is reported to have established around 150 professional colleges and 120 research institutions exclusively for the apparel industry to make its textile workers more efficient so that they could encash the market opportunities likely to be thrown open post-MFA scenario. There should also be a “safety net” that helps slow learners or those who can never learn anything new, and turn them employable in the long run in the globalized economy. Besides, it should also provide old-age security. To achieve these objectives, fiscal commitment should be made in adequate sums under improved governance.

At least, as a futuristic measure, the government should strengthen elementary education on priority basis. Reports indicate that today the government spends around Rs. 3000 per child per year by way of running a poor quality primary school system (Parikh and Shah, 2002). Instead, it is time we encouraged private initiatives to establish quality schools and run them on a template that ensures infusion of analytical skills in alignment with current trends. As a sequel to this, the government may issue a voucher for Rs. 3,000 (that is currently being spent on primary education) in favor of parents so as to encourage them to choose a school of their choice and thus make them accountable for their children’s education. It is time we implemented the 1986 National Educational Policy, without further loss of time, to ensure that we are not left behind the rest of the world in future competition.

Irrespective of the fiscal concerns, the public policy must encourage social sector expenditure comprising mainly education, medical facilities, public health, family welfare and sanitation. It should indeed pave the way for creation of a ‘safety net’ for those segments of the society which are highly vulnerable to the risk of globalization. It also deserves to be remembered by all of us that we have no escape from this reality if we have to achieve economic prosperity in a globalized economy. It is time we worked towards building up national competency by imparting market-determined skills to the workforce and making it fit for its due in global markets. The state should use every resource at its command to ‘mobilize’ the human resources, as Gandhiji led the subordinated classes against the colonial rule to make India a ‘competition state’, which alone enables it to carve a secure place in the global market.

Some pundits, keeping in view the twin elements that intertwine into democracy namely a ‘liberal element’ and the element of ‘popular sovereignty’, argue that “over the longer run globalization and democracy may be at odds with each other” (Marc F Plattner, 2002). It is feared that without the majoritarian element there is a strong risk of ideological schemes being thrust on citizens by leaders, as according to Locke (1980), human beings are “by nature, all free, equal and independent” and hence “no one can be… subjected to the political power of another, without his own consent”. That is why the state should exploit the ‘instrumental value’ of democracy to enhance the learning potential of its citizens from one another and in turn help society to form its values and priorities—in the present context values regarding globalization that questions the competency of job reservations in providing a safety net to the vulnerable sections while ensuring efficiency in the national endeavors. Amartya Sen (1999) argues that for people to understand even their own ‘economic needs’ require public discussion and exchange of information, views, and analysis. It is in this context that democracy, besides its ‘intrinsic value’, can also play a ‘constructive role’ in helping people make political decisions. Such open discussion, debate, criticism and dissent can alone generate informed and considered choices. Such processes facilitate easy formation of values and priorities vis-à-vis those preferences given independent of public discussions and to that extent they become easy for implementation. To augment the scope for generating such goodwill in the society, the government can as well use the services of elected representatives to the Parliament and State Legislatures from reserved constituencies. The government should encourage intelligentsia of the society to collaborate with the people’s representatives from reserved constituencies, initiating a national dialog on the policy of job reservations in the context of globalization and articulate about its inadequacy in meeting the ‘economic needs’ of vulnerable sections of the society and also its potential to inflict ‘inefficiency’ in the system and generate consensus for replacing it with more amenable solutions that would enable citizens to encash the opportunities thrown open by the economic reforms.

VI. Conclusions

The ongoing attempt of India to integrate itself with the world economies and societies is a complex process which is affecting the lives of citizens in many ways. A growing anxiety in the country is that the increased globalization is leading to heightened inequalities between the haves and have-nots. Talent is becoming the hallmark of those who could sell their services in the global markets. ‘Life long learning’ has become the order of the day for sustaining the growth achieved. Businesses in the liberalized economy are prone to face stiffer competition that is emerging from two sources: One, production is becoming more concentrated in a few leading to fewer players that compete intently with each other for the market share and two, increased imports owing to tariff cuts leading to lower price cost markups. Therefore, creation of “good climate” at workplaces, with no discrimination among the employees except merit, is likely to emerge as the guiding principle for businesses. This increased awareness for efficiency and top-rank talent is in course of time likely to challenge the ‘job reservation policies’.

Thus, globalization, besides fostering growth, is also likely to impact the less endowed citizens adversely. Development is reported to have often bypassed the poorest people—and sometimes increased their disadvantages (2003, World Development Report). Thus, a need emerges for building new institutions that can put good public policy in place. These institutions have to provide a safety net for the less endowed to cope with the emerging risks under globalization till at least such time as they reinvent themselves with new skills and are fit enough to secure employment. It is not the strongest or the most intelligent that can survive in the globalized economy but only those who can quickly adapt to the changing market mechanics. Hence, the government must work diligently towards building up that new order in the society. The government should therefore put the increased revenues flowing out of economic growth for building up competency in workforce. Simultaneously, it should also encourage private initiatives to address the negative outcomes of globalization. Lastly, we should appreciate that in a market where information has become democratized, people would see through the game plan and will appreciate those policies which really matter in making their lives better than mere job reservations that have anyway failed in improving the condition of the larger section of the deprived class in any significant way. Suffice to say, the state should simply facilitate the competitiveness of businesses by providing the environment in which it can bloom.

GRK Murty

References

- Ahluwalia, I J 1992: Redefining the Role of the State: India at the Crossroads. Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi, (Mimeo).

- Amartya Sen, 1999 “Democracy as a Universal Value”, Journal of Democracy, 10.3 3.

- Andres Solimano, “Globalization and National Development at the End of the 20th Century: Tensions and Challenges”, made a presentation at the international summit ‘Globalization and Problems of Development’ held in Havana, Cuba on January 18-22, 1999 and the UNDP Conference of Human Development held in Cartagena, Colombia on March 10, 1999.

- Chandler, Alfred, 1990, Scale and Scope, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press.

- De Melo, Jaime, Panagariya, Arvind and Rodrik, Dani, 1993, “The New Regionalism: A Country Perspective”, in De Melo et al. (eds), New Dimensions in Regional Integration, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Debashish Bhattacherjee, “Globalising Economy, Localising Labour”, Economic and Political Weekly, October 14, 2000.

- Deshpande, S and L K Deshpande (1996): “New Economic Policy and Response of the Labor Market in India”, paper presented at a seminar on ‘Labor Markets and Industrial Relations in South Asia: Emerging Issues and Policy Options’, September 18-20, India International Centre, New Delhi.

- Drucker, Peter F, 1990, The New Realities, New York, Mandarin.

- Edward S Herman, “The Threat of Globalization”, April 1999, http://www.globalpolicy.org/globaliz/define/hermantk.htm

- Fallon, P R and R E B Lucas (1991); “The Impact of Changes in Job Security Regulations in India and Zimbabwe”, The World Bank Economic Review, Vol. 5, September, 395-413.

- Hanson A H, “The Crisis of Indian Planning” Political Quarterly, October-December 1963, Reprinted in Hanson AH, Planning and Politicians, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1969.

- Jackson, Robert, 1993, Quasi States: Sovereignty, International Relations and the Third World, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Jagdish Bhagwati, “Growth, Poverty and Reforms”, A Decade of Economic Reforms in India (2002) Academic Foundation, New Delhi.

- John Locke, Second Treatise of Government, C B Macpherson, ed. (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1980).

- Kirit, S Parikh and Ajay Shah, “Second Generation Reforms”, A Decade of Economic Reforms in India (2002) Academic Foundation, New Delhi.

- Klein, Lawrence R (2004) “China and India: Two Asian Economic Giants, Two Different Systems”, Applied Econometrics and International Development, AEEADE, Vol. 4-1.

- Marc F Plattner, 2002, “Globalization and Self Government”, Journal of Democracy, Vol. 13, No. 3.

- Mathur A N (1992): Employment Security and Industrial Restructuring in India: Separating Facts from Folklore—The Exit Policy Controversy, IIM, Calcutta.

- McGee J and Howards, T, 1988, “Making Sense of Complex industries”, in N Hood and J Vahlne (eds), Strategies in Global Competition, London, Routledge.

- Mohan R “Employment Trends in India in 1980s and 1990s in Relation to Output and Other Variables” The ICFAI Journal of Applied Economics, Vol. III, No. I, January 2004.

- Montek S Ahluwalia, “Economic Reforms: A Policy Agenda for the Future”, A Decade of Economic Reforms in India (2002) Academic Foundation, New Delhi.

- Porter, Michael, 1990, The Competitive Advantage of Nations, London, Macmillan.

- Rangarajan C, “Shifts in Industrial Policy Paradigm”, A Decade of Economic Reforms in India (2002), Academic Foundation, New Delhi.

- Roland Robertson Globalization: Social Theory and Global Culture. (1992) Sage Publications Ltd., London.

- Rolen Palan and Jason Abbott with Phil Deans, State Strategies in the Global Political Economy, (1996) Pinter, London.

- Rudra and Nita, 2002, “Globalization and the Decline of the Welfare State in Less-developed Countries”, International Organization, Vol. 56, No. 2.

- Swami Ranganathananda, 1986, Eternal Values for a Changing Society, Vol. II, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Bombay.

- Sztompka, P (1990) “Conceptual Frameworks in Comparative Inquiry: Divergent or Convergent?”, in M Albrow and E King (eds), Globalization, Knowledge and Society. London: Sage.

- Thomas L Friedman, 2000, The Lexus and the Olive Tree, Anchor Books, New York.

- World Development Report, 2003, The World Bank, Washington DC.

† This article is based on a paper originally presented at the National Seminar on “Changing Indian Society:

Social Justice and People’s Movements” held on 27th and 28th February 2004 at Osmania University,

Hyderabad.

[1] The McKinsey Quarterly, 2004 Special Edition: China Today.

[2] Amartya Sen in an interview with Krishna Prasad in Outlook (Millennium Special), November 15, 1999.

No comments:

Post a Comment